Strategy in the Age of Disruption

Why planning is as important as ever

By Matthew Rogozinski

New technologies, private entrepreneurial finance and regulatory inertia have democratised business building over the past decade. Incumbents are facing a seemingly never-drying, ever faster-flowing stream of innovations aimed at cherry-picking their customers, undercutting their transaction costs, displacing supply costs or increasing capacity with previously unused assets, to mention a few. Occasionally, a tsunami of innovations makes an incumbent business model unviable or wipes out a whole industry.

In this age of disruption, should you be thinking about the annual strategic planning exercise? Will strategy papers be out-dated as soon as they are approved? Alternatively, should you allow your organisations to continuously adjust to change rather than create and execute an agreed strategy?

In our view, strategic planning is still a worthwhile exercise in this fast-moving environment. Ultimately, every business must choose where to compete and how and why it will win—it must develop a strategy. Rather than handicapping an incumbent business, doing the work needed to develop, agree and articulate a well-formulated strategy will put it on the front foot in dealing with disruption.

We also believe that continuously reacting to changes in the environment will make it virtually impossible to retain or build genuine competitive advantage (which takes years rather than months to develop) and that this ongoing reactivity will ultimately weaken an established business. We are not saying that such businesses can ignore potentially disruptive activities; they must be ready and able to respond to genuine threats.

So, how to strike the right balance? We recommend the following approach, which focuses on understanding the real disruptive potential of innovations, whether from new entrants or traditional competitors, when assessed against the business’s core strengths and areas of vulnerability.

Step 1: Assess genuine disruption potential

Business leaders tell us, “We scan for new and potential disruptors all the time.” What we often observe, however, are efforts to pick potential winners from the stream of new entrants and respond to them. In our view, that’s a near futile task; it’s more useful to see the emergence of new competitors as an opportunity to test for strengths and vulnerabilities in the existing business model. This diagnostic exercise then becomes a foundation for anticipating the nature and magnitude of future disruptions, whether external or internally developed.

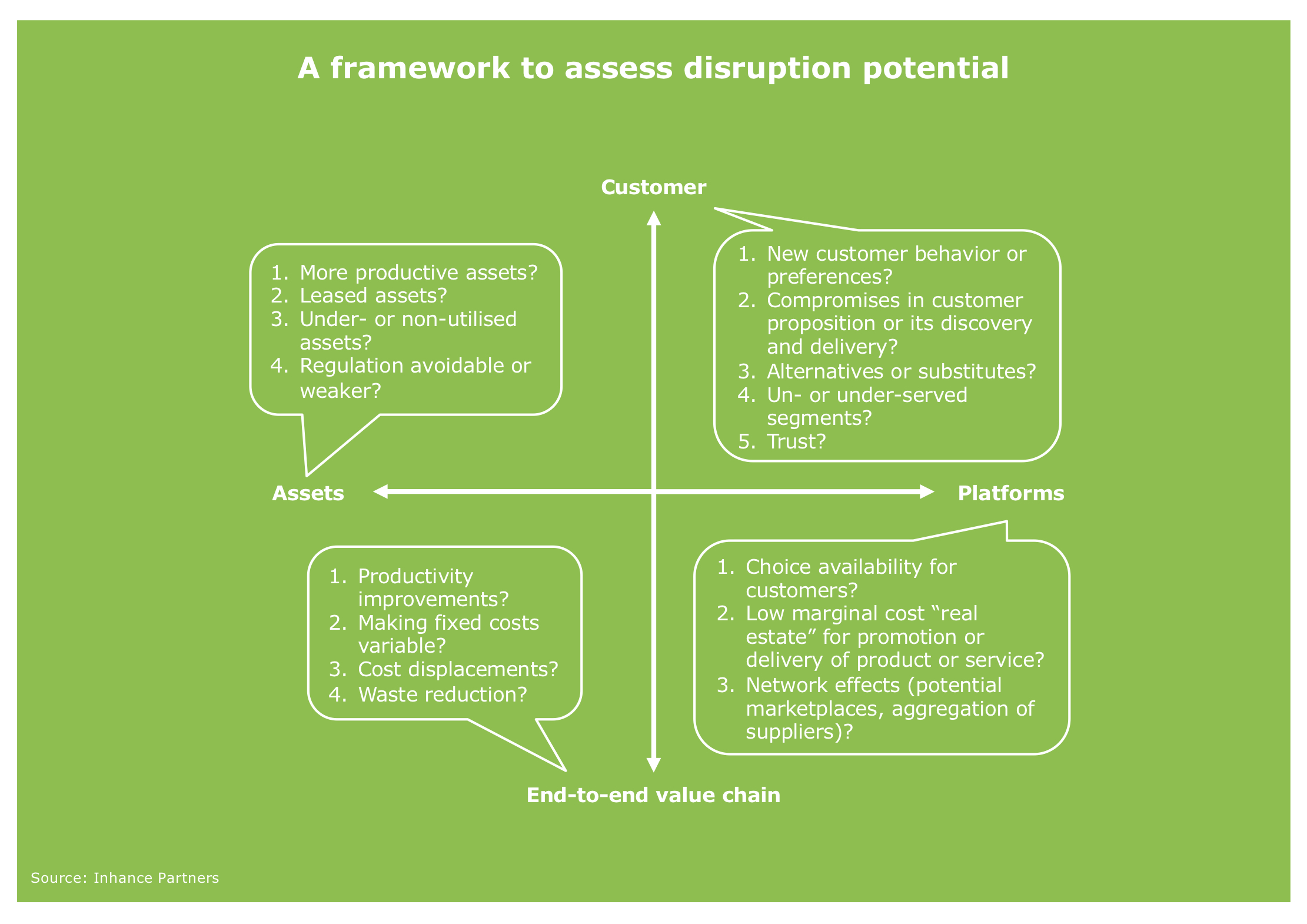

Constantly responding to emerging players locks a business into “as is” thinking when a “what if” mindset is needed. That’s why it’s important to look critically and boldly—but not defensively—at the existing business to identify “disruption hot spots”. These are potential changes on any or all of the customer, value chain, assets and platforms dimensions of a business that have genuine disruption potential, as per the framework below.

A look at successful historical disruptions is useful here. For example, in establishing Jetstar, the incumbent Qantas disrupted the Australian airline industry by leveraging a standardised aircraft fleet (assets), green-site workplace relations (value chain), and self-service in exchange for a price that created new demand (customer). Mortgage brokers disrupted the Australian banking industry by aggregating products from multiple suppliers (platforms) and seemingly championing mortgage buyers (customer). Seek disrupted print newspapers by creating an online job ads marketplace (customer, platforms, assets, value chain). What would the results have been if these developments had been anticipated and the disrupted businesses had acted in advance?

Step 2: Determine whether the strategy needs to change and if so how

Having identified potential disruptions to its business model, an incumbent needs to decide how to respond. The response depends on the answers to two questions: (1) ‘Given the disruption, is the existing business model still viable?’ and (2) ‘If our business model is still viable, to what extent is our competitive advantage sufficient to neutralise the impact of the disruption?’

A fair amount of introspection and objectivity is needed to answer the first question, but we expect the answer to be positive for most incumbent businesses, which leads us to the second question. Answering the second question requires an assessment of competitive strengths relative to those of various classes of disruptors. These classes include start-ups, “unicorns” with private capital patient enough for them to survive ever-increasing periods of unprofitability, marketplaces and global tech players (based in mature and maturing economies), traditional industry players and hybrids (e.g., alliances). Each class will have a different competitive profile. This exercise will assess the real risk of disruption (or the likelihood of success if the incumbent is the disruptor).

It is critical to compare advantages relevant to competing in the age of disruption. They are unlikely to be the same as those that applied a decade ago. We elaborate on this point and illustrate our approach in A Level Playing Field in Digital Banking?

If the answer to the second question is “no”, the business can decide which drivers of advantage to invest in to strengthen or build its defences (or use as a springboard for its disruptive activities).

However, we expect the answer to the second question will be “yes” for most incumbents, with no substantive change to the strategy required. Not everything new that pops up will warrant a strategic response, which may only distract an organisation’s valuable delivery resources from their core tasks and ultimately undermine the sustainability of the business. While some tactical refinements may be useful, executing the existing strategy should remain the focus.

* * *

Rather than an annual “environmental scan”, the monitoring of the business environment should be as close to ongoing as feasible. The significance of new developments should be assessed by passing them through the analysis in Steps 1 and 2 to determine if and how an observed change (e.g., regulatory, competitive or technological) is likely to affect the health of the business model. The stronger a business’s defences (relative advantages), the less likely the need to change strategic direction. When the adjustments are required, they are likely to be bigger and bolder than in a more stable business environment. The approach we’ve outlined will help you stay focused on the areas where you must make those substantial changes.